Anarkali – the legendary figure of Lahore – and the Turkic ruler Jahangir

A Page from History: PakTurk student won the first position in the world

July 3, 2021

First, they threatened to kill; later, they entrusted their children!

July 6, 2021Researcher Doğan Yücel wrote about Anarkali – the legendary figure of Lahore who was the subject of many books, movies and stage plays – and her relationship with the Turkic ruler Jahangir. Yücel narrated how Anarkali was mentioned in the sources and the reflections of her story on today’s world of movies.

In 2006, we had the annual night of our schools at the Alhamra, the largest show hall in Lahore. The Punjab Minister of Education had also graced the occasion as the Chief Guest. Our students presented beautiful songs and sketches. While leaving the hall after the function, one of the parents – who was an artist and academic and whose child was in the class where I was the form teacher – offered me to join him in visiting another hall in the compound. I followed him. Since he was a well-known person in the Alhamra, we were admitted gratis to a stage play and were given seats in the front row. Although we had entered the hall a little late, the show lasted for about two hours. I was not much fluent in Urdu at that time. Despite that, I understood most of the stage play as it was presented in very neat Urdu. I remember that I came across stage plays themed on Anarkali a couple of times later as well.

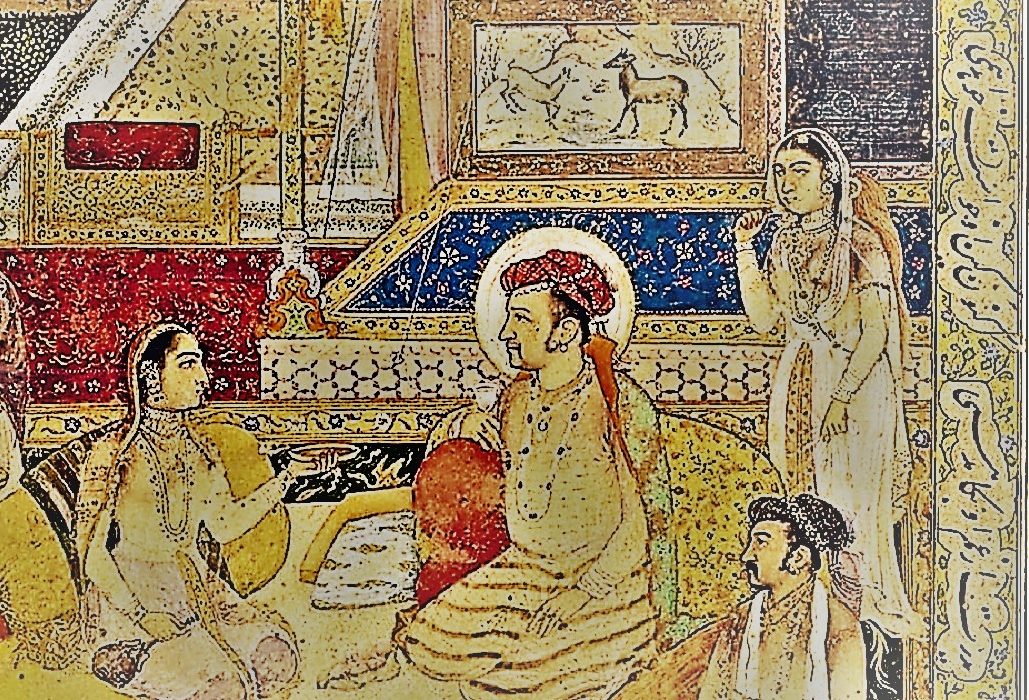

Anarkali (انارکلی) means pomegranate seed in Urdu. This name also denotes a very famous legend in the Subcontinent, both in India and Pakistan. It is the nickname of a legendary courtesan in the 16th century who is said to have been the paramour of the great Turkic ruler Shah Jahangir, formerly known as Prince Regent Salim.

Legend has it that Anarkali had a secret affair with Salim, and therefore his father, Mughal Emperor Akbar, had her executed. There is no historical evidence of Anarkali’s existence, and the authenticity of her story is debated among historians. This courtesan often appears in movies, books, and fictional versions of history. She was successfully portrayed by Madhubala in the 1960 Bollywood film Mughal-e-Azam.

Anarkali is first mentioned in the diary of William Finch, an English traveller and merchant, after his visit to the Mughal Empire on August 24, 1608. There is disagreement among historians as to who Anarkali really was and the authenticity of her legend. There are many views that support and oppose her existence.

The earliest Western records of the love between Prince Salim and Anarkali were penned by two English travellers, William Finch and Edward Terry. William Finch arrived in Lahore in February 1611 (just 11 years after Anarkali’s supposed death) to resell the indigo he had bought in Bayana on behalf of the East India Company. He gave some information about this legend in his notes written in the early 17th century.

‘Emperor Akbar had her executed when he learned of the secret affair’

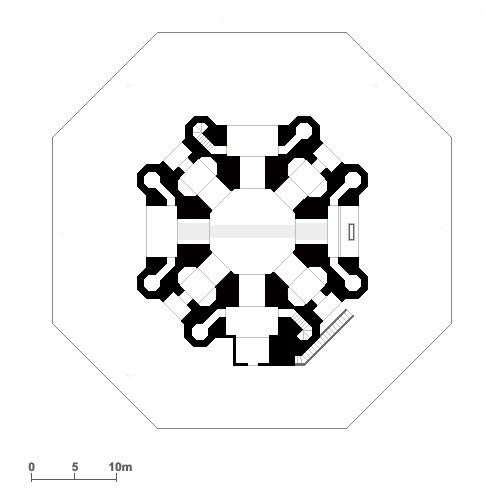

Anarkali had a secret love affair with Prince Salim (Jahangir). It is rumoured that Emperor Akbar, who became aware of the affair, ordered Anarkali to be sealed between the walls of the palace and had her executed in 1599. When Emperor Jahangir rose to the throne six years later, as a token of his love, he ordered a magnificent stone tomb to be built in the middle of the square garden surrounded by walls. The new emperor also wanted the walls of the tomb to be covered with gold. The tomb of Anarkali, which was built in traditional style in accordance with Islamic designs, was finished in 1615 and has eight corners. The octagonal tombs were conceived to represent the eight gardens of Paradise. Emperor Jahangir is that Turkic sultan who had the Hiran Minar built in Sheikhupura in the memory of his favourite deer which he had accidentally shot. He also had the Taj Mahal, which is considered one of the seven wonders of the world, built in Agra for his wife Arjumand Bano Jahan, who died during childbirth.

The tomb is in the middle of a large garden like the Tomb of Asif Khan. It was used as headquarters by Ranjit Singh’s son, Kharak Singh, in the early 1800s, and was later converted into the residence of General Ventura, a French officer in the Sikh army. It was converted into a Christian church in 1851, and the arched openings were largely closed and remodelled. Today it is used as a library for the Punjab Registration Office.

Edward Terry, who visited Lahore a few years after William Finch, wrote that Akbar had threatened to disinherit Jahangir because of his affair with his favourite wife, Anarkali, and changed his word when he was on his deathbed.

Anarkali’s tombstone contains a sad couplet:

If I was able to look at my loved one’s face one more time

I would utter gratitudes to Allah until the Day of Judgment. (Majnun Salim Akbar)

According to Andrew Topsfield, in his book Paintings from Mughal India (p. 171), Robert Skelton determined that these lines belonged to the 13th century poet Sadi of Shiraz.

There are different rumours about who Anarkali’s lovers and herself actually are. It is alleged that she was the mother Prince Daniyal, Sahib-e Jamal, Sharif un-Nisa or Noor Jahan. There are differing opinions about these as well.

Anarkali in the cultural world of Asia

Anarkali has also been the subject of a number of books, plays and films in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The oldest and most famous of these is a historical play called Anarkali, written in Urdu by Imtiaz Ali Taj and staged in 1922. The play was made into a movie called The Loves of the Mughal Prince, which was released in India in 1928 and starring Taj as Akbar. In 1928, another silent Indian film about Courtesan Anarkali was shot by R.S. Choudhury and produced in 1935 under the same title with a Hindi voiceover. Bina Rai portrayed Anarkali in the 1953 Indian film Anarkali. In 1955, Akkineni Nageswara Rao and Anjali Devi starred in Anarkali. Later, K. Asif’s masterpiece Mughal-e-Azam was released in India (1960) with Madhubala as Anarkali and Dilip Kumar as Prince Salim. In 1966, Kunchacko directed Anarkali, a Tamil-language Indian film. In 1979, Telugu superstar N. T. Rama Rao directed and starred in Akbar Salim Anarkali, in which he himself played Akbar with Nandamuri Balakrishna as Salim and Deepa as Anarkali.

In Pakistan, Anarkali was released in 1958, starring Noor Jehan. Iman Ali played Anarkali in Shoaib Mansoor’s short music video series on Ishq (love) in 2003.

In 2013, in Ekta Kapoor’s TV Series Jodha Akbar produced by Heena Parmar, Saniya Touqeer played the young Anarkali. In a daily Colors TV drama serial titled ‘Dastan-e-Mohabbat… Salim Anarkali’, Prince Salim was portrayed by Shaheer Sheikh and his lover Anarkali was portrayed by Sonarika Bhadoria. This series aired as 566 episodes between June 18, 2013 and August 7, 2015.

Lahore’s most famous market

One of the most important and crowded shopping centres of Lahore is undoubtedly Anarkali Market. It is possible to find everything from clothing to souvenirs, from home textiles to stationery in this market. It is like Eminönü-Mahmutpaşa Market in Istanbul. When we had visitors from Turkey, we used to take them to the Anarkali Market to buy souvenirs. Before going to Turkey for the summer vacation, we used to stop by this market and buy souvenirs for our relatives. Prices were quite affordable. Banu Bazaar, which can only be reached after entering the Mall Road on the main road of Anarkali Bazaar and passing through a narrow lane on the left, brings to mind the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul or the Koza Han in Bursa. Thousands of shops are intertwined. However, the most important difference is that in the Banu Bazaar, even three people cannot pass side by side on the narrow lanes between the shops. It is not possible to enter the market premises by car. At the back of the market and around the intersection where the Nila Gumbat (The Blue Dome) is, we used to get off the rickshaw to be able to enter the market. The streets and narrow lanes of the market are always crowded with people.

It is very common to come across women’s clothing companies named Anarkali in Pakistan and India. Saris and shalwar kameez are advertised with Anarkali as brand. Even in countries such as England and America, people from the Subcontinent opened women’s clothing and jewellery stores under this name.

Sources:

–Anarkali (1958). imdb; based on the Imtiaz Ali Taj play/script as adapted by Hakim Ahmad Shuja for his son Anwar Kamal Pasha‘s production/direction

-Balabanlilar, L. (2012). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire: Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781848857261.

-Banks Findly, E. (11 February 1993). Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India. Oxford. ISBN 9780195074888.

-Flinch, W. (1921). Foster, William (ed.). William Flinch (PDF). Early Travels in India 1583 to1619. Humphrey Milford Oxford University Press.

-Glover, W. (January 2007). Making Lahore Modern, Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. Univ Of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816650224.

-Hasan, Sh. Kh. (2001). The Islamic Architectural Heritage of Pakistan: Funerary Memorial Architecture. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-969-407-262-3.

–https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anarkali

-https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/sid/880/pakistan/lahore/anarkali-tomb

–Jahangir (1829). Memoirs of the Emperor Jahangueir. Translated by David Prince. London: Oriental Translation Committee.

-Khan, A. N. (1990). Islamic Architecture of Pakistan: An Analytical Exposition. National Hijra Council.

-Koch, E. (2002). Mughal Architecture. Oxford University Press New Delhi.

-Koch, E. (2010). Necipoğlu, Gülru (ed.). The Mughal Emperor as Soloman, Majnun, and Orpheus, or The album as think tank for allegory. Muqarnas. Leal Karen. BRILL. pp. 277-312 & Footnote:62. ISBN 978-90-04-18511-1.

–Legend: Anarkali: myth, mystery and history”. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

-Loves of a Moghul Prince” – via www.imdb.com.

-Michell, G. (ed.). (1978). Architecture of the Islamic World: Its history and Social Meaning. Thames and Hudson.

-Muhammad, W. Kh. (1973). Lahore and its Important Monuments. Anjuman Press.

-Mumtaz, K. Kh. (1985). Architecture in Pakistan. Concept Media Pte Ltd.

-Rajadhyaksha, A. & Willemen, P. (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute.

-Rajput, A. B. (1963). Architecture in Pakistan. Pakistan Publications.

-Terry, E.(1655). A Voyage to East-India. London: J. Wilkir. p. 408.

-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jodha_Akbar

No Comment.