Teacher Hilal: We bore all hardships for the sake of a sublime meaning

The fatherly advice that changed Allama Iqbal’s life: Recite the Qur’an as if Allah is addressing you!

April 12, 2021

Ramadan: Life that starts with the Crescent (1)

April 15, 2021Mrs. Hilal is a teacher who tried not to neglect her own children while trying to get her students on the track of progress. She left Pakistan ‘by compulsion’ four years ago and currently continues teaching in an African country. We talked with Teacher Hilal, a mother of four, about her past experiences in Pakistan, the first foreign country to where she had migrated and lived for seven years.

Could you briefly describe your life before going to Pakistan?

I am from Elazig. I graduated from Karadeniz Technical University, Department of Social Studies Teaching in 2002. In the same year, I started teaching in an exam and tutorial centre in Trabzon. Later, I got married. I and my spouse worked in different cities in Turkey until 2010. We had two children. We migrated to Pakistan in 2010 as a family. We lived in Pakistan until mid-2017.

How and when did you decide to go to Pakistan? How did your family receive the idea?

Since my studentship, I nurtured the ideal of serving abroad. It was always my dream. Working abroad was a reward for me, not an obligation. I am currently in Africa and am still thinking the same. I’m here not because I have to, but because I prefer it. The life I live is also my choice. May my Lord Allah Almighty make me able to shoulder this responsibility. This is a road I have taken by considering all consequences. One day my husband called while in class and said, “They propose we should migrate abroad. Whatever you say, just think about it, if you wish.” “Accept the proposal,” I retorted. That was not a pre-planned thing. It had been proposed and we accepted. I was not so much upset while leaving from Turkey, my family and friends, because I was destined for a life I dreamt of. That journey was such a beautiful occasion. Our families did not support the idea of our departure very much, but we managed to convince them somehow.

What kind of preparations did you make before you started your journey? May you share your feelings and thoughts during that phase?

On my way to Pakistan, I set out considering the likelihood of living in a tent. I did not have any high goals or expectations. I never researched where I was going or what kind of place it was. This may seem absurd to today’s generation. One should not evaluate that period from a perspective from this period. I did not do any preliminary research because I minimized my expectations and prepared myself for everything. As long as there were some Hizmet-inspired institutions over there, I really did not feel the need to research any other detail. I had only heard, contrary to Turkey, it was a right-hand-drive country. It did not matter much to me.

What were your first impressions of Pakistan?

The time I realized I was emigrating was the moment I boarded the plane. The children were hungry because we had waited a long time at the airport. We wanted to eat on board. We saw the coloured rice for the first time in our lives there. It was sweet too. It was the first time I said to myself, “You have migrated right here and now.”

Each country has its own atmosphere and scent. Pakistan was very hot and had a spicy scent. People wore shalwar kameez. Government officials, soldiers, and police officers sported long beards. It scared me because it was an unfamiliar sight. Because we had been taught in Turkey that ‘foreigners are enemies and one cannot make friends with them’ and that permeated our subconscious. We had those fears during the initial days there.

BE IT A DESERT OR A MOUNTAIN, THAT PLACE IS MY ‘KA’ABA’

In which city did you start working?

We always lived in Islamabad. At first, we stayed with a family for about 10 days. Later, we rented and set up our own house. I did not teach at first. I started out as a housewife. Our friends there periodically organized ‘Cooking Classes’. They were also holding periodical Risale-i Nur Reading Circles in English. I admired them so much. Since I did not know the local language, I first did not know how to provide any assistance. I could not communicate with the local community. I said to myself, “Let me crew the kitchen then; I may wash the dishes at least” and so I was washing the dishes after the visits of those discussion groups.

According to me, the Hizmet is: Doing whatever is the need of the hour and providing selfless service to the extent of what is at hand even if there are no means. There were times I felt washing dishes there had been worth more than serving elsewhere. I was also happy while washing the dishes, because I felt that I had been of assistance that way. I had nothing else to do. I used to propose to my colleagues who led the conversation groups, “Let me take care of your children, while you do your work.” Some seniors used to tell to those who would leave for abroad for the sake of the Hizmet metaphorically: “The places for which you are destined should be your Ka’ba.” They meant to say, “You must cherish that place the same as you cherish the Ka’ba itself.” That was why it did not matter where I went. I cherished it metaphorically as my Ka’ba, whether it was a mountain or a desert. I tried to give it its due that way. Allah protected me from any embarrassment, alhamdulillah. I never said “Why did I come here?” in anywhere I went. I was happy. Seven or eight months after my arrival in Pakistan, I started to work as a Turkish teacher at the PakTurk Girls High School in Islamabad.

Was there anything you had difficulty adjusting?

It was the first time I lived in a different place than my home country. Of course, there was a period of acclimatization and getting used to things. Not knowing a foreign language felt very difficult. Everyone seemed a stranger. For example, one day I went to the grocery store; indeed, it was no different than a small wooden hut at a street corner. I wished to buy some onions, but I could not express it to the old man there. I tried to explain in English, but he did not understand me. I did not know how to say that in Urdu. Finally, I mimed weeping and pretended to chop something with a knife in my hand. Actually, I wept there for real. It was then the old man took some onions from under the counter and showed me. Those were some small things but could be very challenging while adapting to a new country. I am from Elazig. Pakistan is generally a closed society. It had several aspects that overlapped a lot with the society I came from. I did not find the country much difficult to adapt.

I also consider it from this perspective: When you start running appraisals of the target cultures, you render yourself unable to offer what you really wish to offer to them. The things you see as wrong, if any, are wrong for you only. If you think something needs correction, you are to show it by living and representing it. Cultures should be accepted as they are. Africa is a very difficult culture too. However, if you have chosen to be there, you must accept it as it is. If there is something different according to our belief, maybe we can attain it gradually by experiencing it, not by urgently saying “You are doing it wrong!” but by saying “Let’s remember how Rasulullah (sallAllahu alayhi wa sallam) did it”.

How was your interaction with the students and their families in Pakistan?

Since I taught Turkish, I was always endeavouring to speak Turkish with my students. I also wanted to learn English, but I did not have the opportunity. Not knowing English or Urdu did not interfere with my guidance and counselling activities. One day a week we had “guidance” period in class with the students. I used to get up early on that morning, prepare treats such as cakes and donuts, and take them to school. The students knew I would come on Thursdays to the first class with treats. Even though I did not narrate anything to them, the students realized and appreciated the sacrifices I had made for them there. The Turkish-speaking students helped me bridge the communication gap with those who did not. Not knowing the language troubled in fully understanding the people and the students; however, it did not stop me and my students from warming up to one another. I really loved Pakistan. Our school was set in a bungalow. Actually, one of the classrooms where I taught was sourced from the kitchen. The classroom had the kitchen workbench and the faucets intact. One of the topics in our Turkish classes was introducing the Turkish food. We actually cooked in class during that lesson.

There were problems, but they did not bother us. When someone is happy, troubles can be reduced to nothing. Some things might bother others but they did not bother me. I was very happy for every moment I had spent there. I would take turns inviting the parents of my students to my house. I did not speak Urdu, but we understood one another through translation apps. We had very good friendships. I have my friends with whom I still keep in touch from there.

WE SPENT EACH RECESS WITH OUR STUDENTS

What were the feelings and thoughts of the people of Pakistan towards the Turkish schools and teachers? Was there anything you had a hard time communicating with or was it easier than you expected?

They brimmed with goodwill and fellow feelings for us Turks. That was not something that had started with the advent of the Hizmet Movement in Pakistan; it was an affection that continued existing since the War of Gallipoli and even much earlier. Even the drivers on the streets would be more concerned and respectful when they found out that we were Turkish. The people of Pakistan have generally fellow feelings for many expatriates from different countries. Far beyond than that, the people of Pakistan foster a tradition of love and affection towards the people of Turkey based on the common history. Thanks to that, I had no difficulty in reaching out to the students and providing guidance to them. From the moment a teacher walked in from the gates of the school, the students would teem around her. I do not remember sitting restfully in the teachers’ lounge and drinking tea during recesses. The students would not let me be, affectionately. As their fictive mothers, we were with our students during each recess. I would plan in advance with which student I would meet at which recess. Sometimes they would wait for me at the door of the classroom where I was teaching, and take me away with themselves before I could enter the teachers’ lounge.

What would your students share with you?

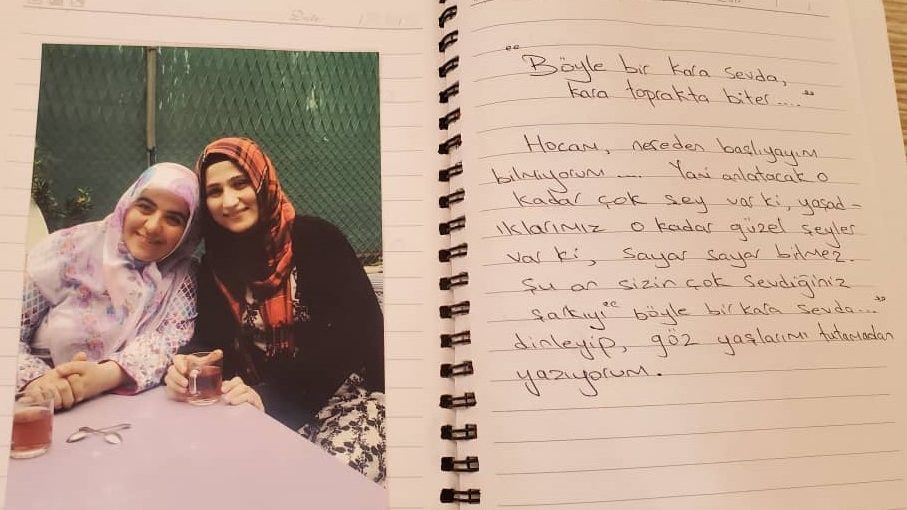

I knew all the troubles and family circumstances of all my students. They would be overwhelmed and come to tell me about their problems. I would try to solve those problems for them. My students still call me. They started to become teachers themselves. Whenever they encounter a problem, they phone me and we try to solve that together. This delicate contact has never disconnected. Since they were in throes of adolescence at that time, they would have problems with their families. I did not have any students whose problems I had not been aware of. This is trust. When the student walked in and told me about her problems, she was sure that issue would never leave that room or me, or that she was sure I would provide assistance to her through prayer and constructive feedback even if I could not do anything when she told me. My students had compiled three diaries for me at different times. I still keep them with me. One of the students wrote, “I would never imagine I could warm up this close to a person of a different nationality.” On top of that sincerity, the concept of nationality and other differences disappeared.

What did you experience during the phase of your children’s acclimatization to Pakistan?

I migrated to Pakistan with our two children. Two more were born there. My deliveries were much more comfortable than they had been in Turkey. My friends in our community stood by me all the way. For example, they would breezily schedule the daily cooking and delivery of food to our house while I was in my post-delivery phase. It was not easy for our children to get used to different places; of course, they had difficulties, but the attitudes of their parents mattered so much in that as well. The easier we parents adapted, the better so could our children. My husband and I did not criticize anything about the country in our house. If there was something, we did not speak that in front of our children, nor did we allow any inappropriate criticism. After talking negatively about the country and the circumstances in front of the children, it simply does not work even when you say “We have to live here”. We gave and have been giving this message to our children: “We live the life this way and we will continue living this way. If you wish to change the course of your life when you are able to stand on your own feet in the future, we will stand by you.”

My kids are not very extroverted, and I am not like that either. For the first time, they had encountered people speaking a different language, practicing a different culture, and looking different. That made them a little nervous. When we first went there, my older child was in the kindergarten and he did not want to go to the school. One day, the school van came and sounded the horn, but he did not want to go. He kept on crying. I took him outside with its bag. I said, “There is nothing to do, you will have to get used to it!”, and I closed the door after him. Of course I was very sorry, but there was no other way.

PARENTS NOTICED MY BUSY SCHEDULE DESPITE MY CHILDREN

You have 4 small children. You teach at the school. You’re not done when your shift is over. You continue to guide students with extra programs after the school, that is, during the time you have to spare for your home and your children, and you meet with their families one-on-one. Of course, all this has not been easy. In which situations did you face more hardship?

I would leave the children to the caretakers whom people called as ‘aunty’. Of course, they would not like to be left there and they would cry. I always thought that when Ibrahim (alayhissalaam) was to fulfil the commandment of Allah Almighty, he did not look his son Ismail (alayhissalaam)’s eyes. That compassion might compel him to divert from his mission.

I was sorry for my children; I had an intense schedule. Indeed, they were also born one after another. When my oldest was 7 years old, I had already become a mother of four. That situation was really challenging for me, but it never could prevent me from fulfilling my Hizmet-related responsibilities. While I was lulling my child to sleep on my feet, I was also delivering my lecture from the Risale-i Nur in our regular study circle. Later, I was getting up and preparing the tea and the refreshments. Those were not the things that could not be accomplished, and they had been accomplished. My other friends too did the same and it will be done the same in the future as well.

A mother’s compassion for her children is extremely vital, but I was careful not to utilize it in a manner to separate me from my mission and responsibilities. I do not know whether that was positive or negative, wrong or right, but we had done it. I entrusted them to Allah Almighty; I prayed every time by saying, “I leave them behind, but I trust them to Your care and protection, O my Lord!” Those hardships had to be experienced wherever I would be. They would have been experienced the same, if I had lived in Turkey too. At least for the sake of a sublime meaning and intention, those hardships were borne.

Sometimes we had to take intercity trips to other cities for subject specialists’ coordination meetings as an entourage of seven – my four kids, myself and two caretakers. Friends considered that feat really challenging. They would even laugh at me sometimes. On the one hand, I would feed my child, on the other hand I would deliver my guidance and counselling session. Such feats attracted a lot of attention from the students.

There were always guests at our home anyway. Actually, that was the case for all friends. It was not just my thing. My own children’s weekly programs would also be held at my home. Such guest receptions attracted the attention of both students and parents. I invited all parents of my students to my home in turns. At the end of the year, I made an appraisal and asked them, “How did you feel about visiting my home?” Almost all of the parents said, “It was very impressive that you endeavoured for receiving guests and arranging programs for us despite your children.” They were moved not only by the conversations we had during those programs, but also by our tongue of disposition.

In fact, I would even request the caregivers to take my children outdoors when the parents were to visit me at home. The children would cry and get hungry, even if they had their caregivers, they wanted me. I would try to keep the children away from home so that I could take better care of the parents. That caught the attention of the parents. I did not know which of these had been worthwhile for attaining Allah’s approval.

When and for what reason did you leave Pakistan?

Originating from the incidents in Turkey, a troubled process also started for us in Pakistan. Our circumstances become more stifling on each day. One of the parents had said to me during the early days of that crisis, “Don’t fret, we are sure you have done nothing wrong. We will take care of you. This is a political issue. We are all aware of this.” Three or four months passed after that conversation and, after the abduction of the Kacmaz family, our apprehensions increased. One night we took our children and our passports and left our home. Similar to all of our friends and colleagues, we got into our car in a hurry and hit the road at midnight. We did not know where to go. There were soldiers and personnel carriers everywhere, that was something ordinary in the country.

IN THAT TIME OF TROUBLE, THEY HOSTED US BY SAYING ‘THIS IS YOUR HOME’

I phoned to a parent, explained the situation and asked “Can we come to you?” She accepted. At that time, a family had recently arrived in Pakistan and they did not know anyone in the country. We took them along with us as well and went to that parent’s residence. The family greeted us at the door and said, ”You did not even need to ask, this is your home.” We, the family who were new to Pakistan, and another family stayed at that place for a few days. At the point where it was no longer possible to stay in Pakistan, we had two options: seeking asylum in different countries or migrating to the countries where the Turkish schools were still open to work there. We wanted to continue our profession and migrated to Africa.

Two of your children does not know about Turkey at all, because they grew up in Pakistan. Do you live in Africa now? Are there things they have trouble getting used to?

The younger ones thought they were Pakistani. My youngest child was 3 months old when we had visited Turkey the last. He had no episode of Turkey in his life. One day, while talking to him, I said, “Son, everyone speaks Turkish in Turkey; in the street, in the market, everywhere after getting off the plane.” That was very interesting to him. “How so? Really, at the bakery too?” he asked. “Yes, everywhere!” I replied. He rushed and told his brother, “Have you heard Yusuf? There is a country where they speak Turkish everywhere!”

They talked to my mother on the phone only, they never had any memories together with her. Even knowing that I had a mother surprised them. I think they see the benefit of meeting a different nation, a different culture, and becoming a world citizen. Since we never open the door to the criticism of any country we are in, our children also adapt to that. Our children are also getting stronger with us. For example, we did not have any income when we were severed from the schools in Pakistan. We tried to use everything frugally. The bungalows in Pakistan are generally large. We had chosen our residences as large to be able to receive more guests. Since we could not pay the high rent of a large house, we moved to a smaller house with low rent. My little daughter must have heard us while talking about it at home. Thinking that she should use the lines more economically so that her my notebook would not fill up quickly, she reduced the size of her handwriting on her notebook so much small that she was scolded by the teacher. She was so upset about being scolded while being a very successful and idealist student.

What are the impacts and contributions of Pakistan on your personal life? Do you have anything to say like, “I would not have known that if I had not gone to Pakistan”?

Pakistan was my first place of emigration; it was my second homeland. I still consider it that way. The people were very sincere, valuable, and altruistic. May Allah be pleased with all of them. They took care of us profoundly. Of course, there are good and bad people everywhere. You cannot attribute them to a country without any exception. If it was today, I would go to Pakistan again. I have learned that people outside Turkey are not hostile. Yes, Pakistan may be a poor country, but I have seen that the external appearance does not matter; the inner realm of people can be very rich and profound.

No Comment.