English Teacher Gönül Barış (1): I had difficulties in the first years, but I still choose Pakistan to live

‘Turkey where you are not is no different to us from other countries’

March 24, 2022

Bahauddin Zakariyya: Multan’s Patron Saint

April 1, 2022Gönül Barış experienced many firsts of her life in Pakistan, where she went as a university student. After graduating from university, she gained her first teaching experience and got to know her first students, whom she will never forget for a lifetime. This country – where she met her life partner, spent the first years of her marriage and experienced motherhood – has an indispensable place in Teacher Gönül’s heart.

Gönül Barış, describing the 12 bittersweet years she lived in Pakistan until her departure in 2017, says, “I’ve been to different countries, but if they ask me right now, ‘Where would you choose?’ I would choose Pakistan. The sincerity of people, the respect, love, value, and cordiality shown everywhere… I guess these are what connects me there.” In the first part of our interview, you will read about Teacher Gönül’s journey to Pakistan and her first years there as a student.

-Can you tell us about your life before you went to Pakistan?

I am from Niğde. I studied high school at Private Sungurbey College. At the same time, I attended a private tutoring centre to prepare for the university entrance exams. I couldn’t score adequate to be placed in the degree program I wanted. My advisor asked, “Would you consider studying at a university abroad?” I replied “Okay,” without thinking. It was 2003.

-How could you decide so easily? Did you know about education abroad back then?

Actually, I am the only child of my family. My parents had hardly allowed me even for the trip to Istanbul. How I said ‘Okay’ there, I don’t know either. I didn’t know to which country I could go. Until that time, I had watched videos about the schools opened by Turkish philanthropists abroad. I wanted to teach in those places too. Around that time, my advisor teacher asked me, “Would you like to go to Senegal?” I didn’t know at all where Senegal was and what kind of a place it was. I even thought it was in Central Asia.

-How did your family react to this decision?

My father was a businessman. He dealt in iron joinery. I went to his store to talk to him first. “I will go abroad to study at a university,” I said and my father said, “Where did you get this idea? No way!” When my mother found out, she said “No way!” They doted on me because I am the only child. I requested them to visit my tutoring centre and meet my advisors. They were convinced there. “Okay, you may go then,” they said at last. We also learned Senegal is an African country. My mother wept as we packed my suitcase together.

-What was Senegal like? What were your first impressions?

They told us about Senegal in such a way that it was as if there was nothing there. That’s why, for example, we were happy whenever we saw chicken. I was very surprised when I saw they had bought some chicken for our dormitory. Whenever we saw some fruits, we rejoiced there was fruit in Senegal.

-Perhaps your advisors told you about the worst conditions and wanted you to reset your expectations and be grateful for the things you saw as good?

Yes, they definitely wanted so. They must have told us that way, thinking we should be happy every time we saw those. We studied French there for two years. A friend and I wanted to study English. We searched and while we thought about what we could do, his parents met someone from Pakistan who regularly took students from Turkey to there for higher education. Her parents decided to send my friend’s brother to Pakistan. The parents said to their daughter, “Would you like us to send you there too? You always wished to study in English.” She called me one day and told me she wanted to go to Pakistan. “Then I’m coming with you,” I said to her. I also talked to my seniors in the dorm. My parents were surprised again; this time they didn’t object but said “Okay, you may go”.

I SAID ‘THIS FEELS BETTER AFTER SENEGAL’

-Did you know about Pakistan? What did you first encounter there?

We made visa applications in Ankara. Meanwhile, we also searched to know what kind of place Pakistan was. We learned it was ‘a tad’ better than Senegal. We were to go to Islamabad where we would attend the university and volunteer as mentors for boarding students. When I landed in Karachi, the decision changed. We had to wait for an upcoming group of students from Turkey. As three female students, we waited for a month at a sister’s house in Karachi. It was August 2005 and very hot. I never forget: When we came out of the airport terminal, I was very happy to see a McDonalds outlet right across the street. We said, “After Senegal, this place feels better.” When the expected student group arrived, we divided tasks among ourselves. I was to go to Lahore. My friend, with whom I had arrived from Senegal, would stay in Karachi. I wept a lot because I didn’t want to go. I loved Karachi and wanted to stay there.

-What did you do during that one-month wait?

Actually, we didn’t go out much. We went to visit a school and met the teachers. We knew no English anyway. We studied English every evening in the house where we stayed. The host sister tutored us in basics. She lived in Pakistan for many years. She and her husband had pledged to host every new colleague to Karachi in their house. We were grateful because they hosted us so well. I went to Lahore with a group of friends. An older sister I knew from Senegal and her husband were also in Lahore. It was good to see familiar faces.

-How was your life in Lahore? What difficulties did you have the most in university or social life?

The student residence where we would be staying had not been rented yet. A teacher whose wife was in Turkey left their house to us and we as 6 female students settled there. We set up our own system in that house. We set up cooking and cleaning shifts. A while later, when the lady of the house arrived, she felt she was like a guest in her own residence. We stayed there for about a month. Eventually, a proper house for rent was found and the first female university student residence in Lahore was opened. It was a two-storey villa on a side street. We had our household items and a few utensils. For example, we had 3 pots only. We prepared food and tea and boiled water in the same pots, because we could not drink tap water. We constantly filled, emptied and changed the pots. It was difficult. It was something about being the first.

Since we were the first mentors, we had no one to take as role model. We were told it was not safe to go out. Except for the English classes, we always stayed indoors. A brother would do the shopping and drop the items at our doorstep. We ate whatever he brought us. If we ran out of salt, we couldn’t go out. We were afraid because we did not know the language. We did not know the outdoors and the people.

A LOOK IN THE DICTIONARY AND WE REALIZE WE FAILED

Meanwhile, we also enrolled in an English language school. We had a shuttle van. We used to drive to the school with 6 girls sitting in the back and 2 brothers in the front. In fact, our shuttle was something repurposed from a mini pickup with facing long benches in the back covered with a canvas. Our Pakistani schoolmates tried to help us but we couldn’t communicate with them because we understood nothing. The most challenging component for me was the ‘Listening’. The teachers would make us listen something on a cassette, stop it and then ask what we us questions. We wished the teacher not to ask us anything. Because the difference in accent proved harder. Whenever the teacher spoke, we could make some meaning out of her gestures, but it was impossible for us to understand what we had listened.

I have an unforgettable memory in that language school. At the end of the first semester, they displayed the exam results. All Pakistanis had the letter P in front of their names, and Turks had F. We didn’t understand what it meant. We look at the lists, smiling. A Pakistani schoolmate came and said something in English. We still could not understand, but when we opened the dictionary and looked at the word, we realized we had failed in the class. We had a hard time because we had started the first semester halfway through the course. When the second semester started, we understood things better.

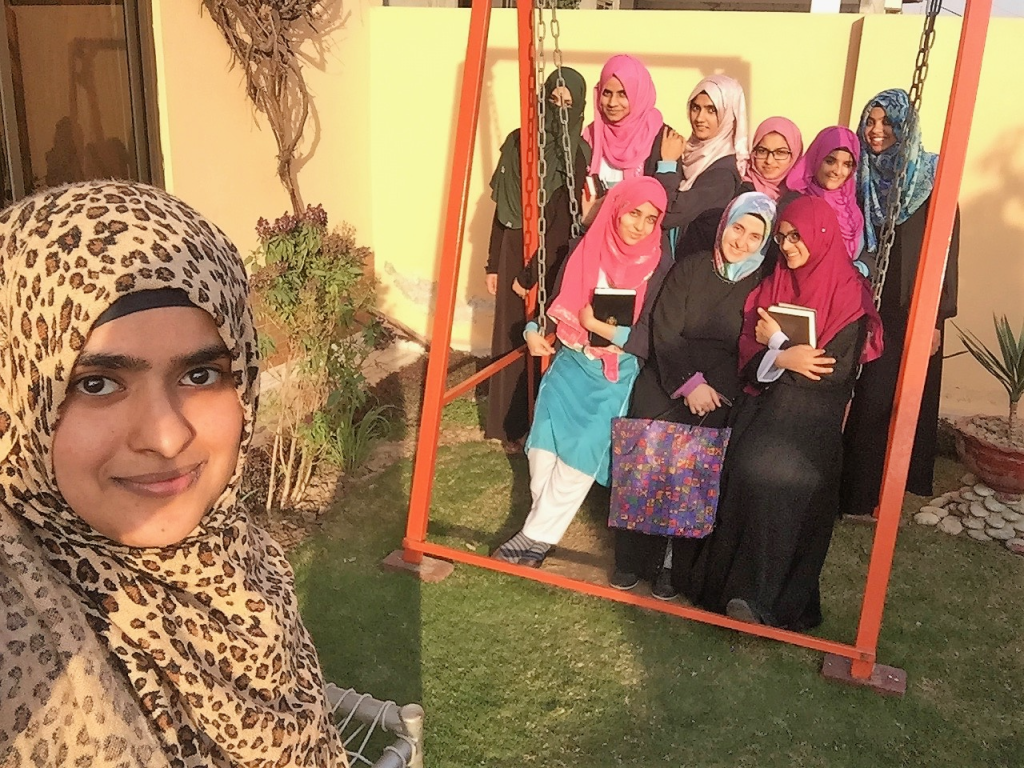

-What did you do besides the language school? Did students visit your house?

Sometimes female students studying at the PakTurk School would visit, but since we did not know the language, we just tried to get our messages through mimes and gestures. We excitedly prepared treats for them, made fruit plates, and sought ways to endear ourselves. Of course, we prepared Turkish dishes because we did not know the local culture. For example, we knew they liked rice and we cooked it, but they would find our rice tasteless, saltless and insipid. Since I had lived in Africa, I was a little more aware. Our first year passed trying to get to know each other this way.

-What emotions did it make you feel considering a different culture, food style and living conditions? How did you tell your family about that?

I told nothing negative to my family about Senegal or Pakistan. I always talked about the beautiful aspects. For example, they did not know we could not go out frequently and under what conditions we had lived. I used to say, “We are on our way to the language school. Everything’s fine.” We could not go to the market because we did not speak the local language. An old vegetable vendor used to pass shouting along the street. Whenever we didn’t come out, he would come knocking on our door and to give us the vegetables. We could never communicate fluently with that uncle. He used to write the numbers on a piece of paper and show them to us, asking if we wanted 1 kilo or 2 kilos of something. We used to point at the numbers for the amount we needed. He couldn’t speak English; we didn’t know Urdu.

WE THOUGHT THE RICKSHAW DRIVER SAID A CURSE

One day we were to visit a sister at her house. She had written down the address and given it to us, saying “Get on a rickshaw and come.” We showed the paper to the rickshaw driver. “Okay,” the man said. We set out for the journey in the shuddering rickshaw. It was a culture we had not been used to. We also used to be very happy whenever we got in a rickshaw; it felt as if we were in a Mercedes. Six girls in groups of three, we used to get in two rickshaws. Soon, the driver stopped and said, “Intizar! Intizar!” We could not understand him. We thought he was cursing us. We said to one another, “Why does he say this? We will pay for the fare anyway!” It turned out he had said so in a sense we had not known until then. It meant ‘wait’ and he meant to say, “Wait, I’ll take a turn and you can get off then”. We were sad and thought he had uttered a curse.

Another day, we were to Islamabad for a program. We boarded the bus. On the way, I said to friends, “This is the wrong bus! This is not the bus to Islamabad!” as if I always travelled on that route. They were alarmed. We asked the passengers on the bus. They said, “This bus goes to Rawalpindi, not Islamabad.” We were on the wrong bus for sure. We kept on thinking what we could do. Should we stop the bus and get off? We kept on thinking. Cell phones weren’t that common back then, so we couldn’t call and ask anyone. We decided at last. We would go until the last stop and decide there or make a phone call. It turns out that the terminal for the bus to Islamabad was in Rawalpindi, the twin city of the capital. We had actually gotten on the right bus and were on our way to Islamabad. We learned that when we reached the last stop. Our first year passed with such adventures of not knowing the language.

To be continued…

No Comment.